|

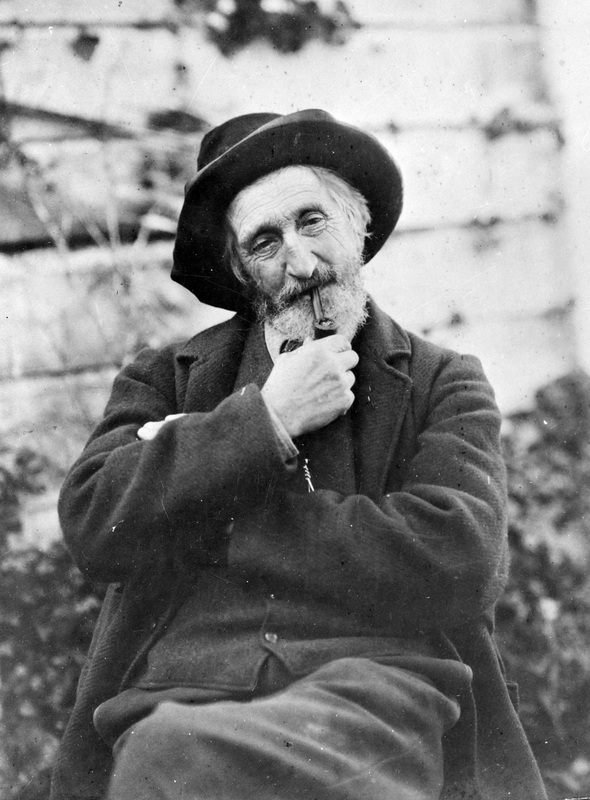

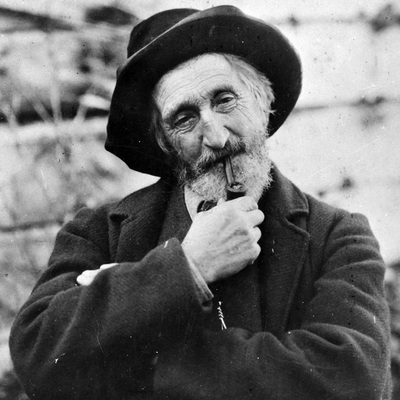

Charlie Douglas

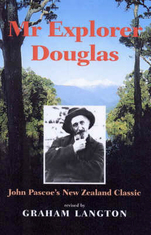

Mr Explorer Douglas,

John Pascoe's New Zealand Classic. John Pascoe, edited by Graham Langton Canterbury University Press |

An original hard man

Many early pakeha explorers spent a few years “discovering “ our hinterland but Charlie Douglas spent over 40 years doing it. He came to New Zealand as a 22-year-old from a comfortable Edinburgh life. Arriving in Dunedin in 1867, he worked as a shepherd and gold prospector before ending up exploring and surveying in South Westland.

Mr Explorer Douglas is a compendium of his writings from this time. Eventually the government Survey Department paid him for his efforts but it was never easy. Days of carrying 60lb+ (30kg+) swags, ferrying months of supplies up river, climbing to mountain passes with no alpine gear and living on tobacco, flour, tea and native birds. He obviously enjoyed his work and wrote lots of personal observations as well as Government reports. He was an acute observer as this description of sand-flies shows: ...an encourager of early rising and an enemy to sedentary habits...At first break of day he proceeds to business, with a fiendish skill he soon discovers a hole or weak spot in the blankets, in he goes followed by all his relations and up you must get... If their place in creation is small, no one can say they neglect their duties, which is more than most men can say..." His dogs were often his only company and were invaluable for travel and survival. He had no truck for hunting as sport but with rifle, snare and dog he relied on bird life for a varied diet during months of wilderness travel. His descriptions of birdlife and it's decimation by man and dog, cat and mustelid is heart-felt and gobsmacking. In his 40 years he saw the decline of many species and probably contributed to the demise of some. His mistaken description (and shooting!) of massive harrier hawks in Haast pass are probably the last sightings of the extinct giant Haast eagle.

One morning he woke to a dozen dead kakapo lying in his camp. The birds had been caught by his dogs who would hunt and fetch them expecting a cooked reward. I never kill bird or beast for sport, and hate to see anyone doing it. If I want a bird for food, I take the surest method of doing it...necessity is the only plea for taking life.” In 1892 he visited the upper Copland River and noted the decline of birdlife after 30 years of European exploration:

Years ago...rivers in south westland were celebrated for their ground birds, no prospector need carry meat with him, even a gun was unnecessary nothing was required but a dog, almost any mongrel would do. The weka prowled round the tent, annexing anything portable and the kiwi made night hideous with its piercing shriek. The Blue Duck crossed over to whistle a welcome. The Caw Caw (Kaka) swore and the Kea skirled, Pigeons, Tuis, Saddlebacks and Thrushes hopped about unmolested. The Digger with his Dogs, Cats, Rats, Ferrets and Guns have nearly exterminated the birds in the lower reaches of the southern rivers. “ Before we left the Copland, and coming away we saw the tracks of a Cat. Such is the result of the advent of the white man a few months and pussy will extend operations and the small birds will vanish forever and worse and worse the Ferret is on his way up from the south. “ Charlie Douglas and Whio:

There [sic] tameness and so called stupidity is simply the result of living in a country where for hundreds of generations they had few or no enemies.” Even during his time Charlie noticed a decline in Whio numbers. In early days they were a reliable food source. But by 1891:

What is up with the Blue Ducks? They are very scarce, and so wild that the dogs can't catch them and they won't let me get within shot of them...Is it possible that an Aesthetic breed of [ferret] those vermin have come to the Waitoto a breed too refined for vulgar game but must have Ducks alone? “ The writings and drawings of Charlie Douglas were preserved and collated by John Pascoe published and in 1957 as Mr Explorer Douglas. With a recent revision by Graham Langton and the Canterbury University Press in 2000. It's a fascinating read.

|